One of the confusing things around private investments — especially real estate syndicators — is advertising “Average Annual Returns” (AAR). I personally find this a bit shady because they can’t be directly compared to other returns such as the stock market, which are compound returns (specifically, using Compound Annual Growth Rate or CAGR). For example, you may see a real estate syndication with a target 14% AAR. Whoa! you think. That’s so much better than stocks. But wait – you’re comparing apples and oranges.

Of course, sponsors are “stuck” using AAR because if they advertise using CAGRs now, their returns will look inferior to their competitors. So this is an industry problem.

Concretely, if you invest $100k for 5 years with an Average Annual Return of 14% that means that you’ll have $170k in 5 years. (100,000 * (1+0.14*5)). But if this were a CAGR of 14% instead of just an AAR, after 5 years that same $100k would have been worth 100,000 * (1 + 0.14)^(5 years) = $192.5k. Oof, you would have received $22.5k less than you expected from the advertised 14% return! That’s why you need to convert this Avg Annual Return to a CAGR for relative comparison.

To do this conversion, we have to start by defining each term:

- AAR is the total return divided by the number of years it took to achieve. In the above example, you gained $70k on top of your original $100k investment in 5 years. That’s (70,000 / 100,000) / 5 = 14%.

- CAGR accounts for compounding by applying this rate each year. You invest $100k, after 1 year at 14% return, you have 100k * (1 + 0.14) = $114k. In year 2, this $114k grows another 14%: 114,000 * (1 + 0.14) = $129,960. In year 3, this nearly $130k also grows at 14%: 129,960 * (1 + 0.14) = $148,154.40. Do this a couple more times to arrive at the final value of $192,541.46. The key here is that you earn 14% not only on the initial principal, but also on the gains from previous years.

With the above conceptual understanding, we can introduce a couple formal definitions for each:

-

AAR = ((FV - PV) / PV) / n

-

CAGR = (FV / PV) ^ (1 / n) – 1

where FV = future value (i.e., the value at the end of the investment), PV = present value (i.e., the value at the start of the investment), and n = number of years the investment is held to achieve the given returns.

Remember algebra from high school? Let’s put it to use to figure out how to convert an AAR to a CAGR.

Notice that the CAGR has a FV/PV term. Ideally we can substitute this with something based on the AAR definition. So let’s start by rearranging the standard AAR definition slightly. The key insight is that we can simplify the AAR definition because (x-y)/y is the same as x/y-1:

AAR = ((FV - PV) / PV) / n

= (FV/PV-1) / n

Now rearrange slightly to isolate the FV/PV term so we can plug it into the CAGR formula:

AAR*n = FV/PV-1

FV/PV = AAR*n+1

Ok, so now let’s plug this into the CAGR formula so we can define CAGR based on AAR instead of present and future values:

CAGR = (FV / PV) ^ (1 / n) – 1

= (AAR*n+1) ^ (1 / n) - 1

Awesome, so this is the general equation for converting AAR to CAGR!

Now we can calculate what the actual CAGR is for the advertised AAR of 14% over 5 years:

- CAGR = (170,000 / 100,000) ^ (1/5) – 1 = 0.112 = 11.2% CAGR

Let’s use the above example to sanity check that this is the correct result:

- 100,000 * (1 + 0.112)^5 = $170,029

Nice! So our derivation is right! (It’s slightly over the expected $170k just because I rounded up to get to 11.2% CAGR.)

This means that the advertised 14% return is comparable to an 11.2% return from the stock market! While this is still a solid return (and diversified from stocks), it’s a far cry from what less math-inclined investors expect from their “target” returns.

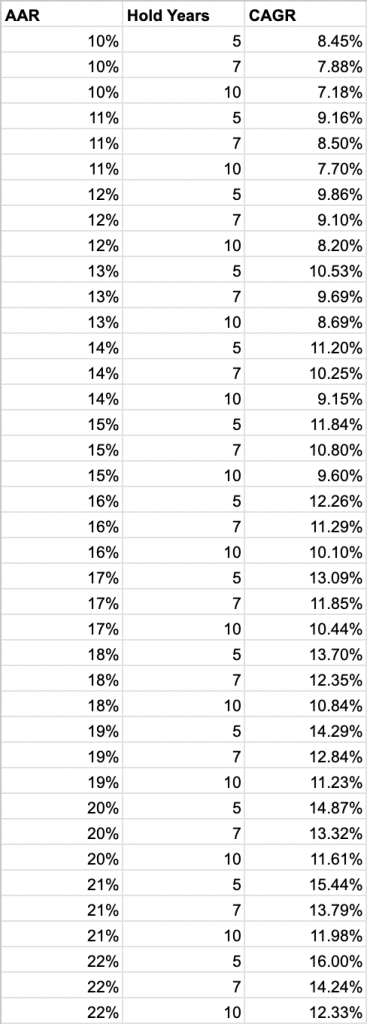

Now we can create a handy table of commonly advertised AARs converted to CAGR values:

Next time you see an AAR for a private offering, convert it to a CAGR above for easier comparison to stocks.

Better yet, ask the sponsor for an IRR-based target which let’s you compare apples-to-apples even better. (The IRR includes the time value of money, accounting for when you receive returns, such as stock dividends or real estate cash flow or distributions from refinancing.)

0 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.